After earning a master's degree in biomedical engineering, Kali Manning stayed to pursue doctoral studies with her 3D tissue engineering research group.

Credit: Frank Mullin/Brown University

Reflecting demand in the economy, Brown's graduate programs in biomedical engineering and biotechnology have more than quintupled their enrollment in four years.

With equally strong interests in biology and visual arts, Rebecca Wojciechowicz enjoyed a quintessentially Brown undergraduate experience, parlaying the open curriculum into a dual concentration that she completed in 2014. But then she extended that classic Brown trajectory into a path less traveled at the University: she stayed to earn a master's degree in biotechnology.

"I'm really into this concept called biomimicry," said Wojciechowicz, who completed her degree requirements in December and will formally receive her master's in May. "It makes sense to emulate nature when creating and innovating man-made designs. And it's a great way to put both of my interests together."

She realized that as a master's student, she could gain valuable engineering skills and research experience to better apply her creativity to bio-inspired designs. Through the program, she also found a job designing and developing products at Bard Davol, a medical device company based in Rhode Island.

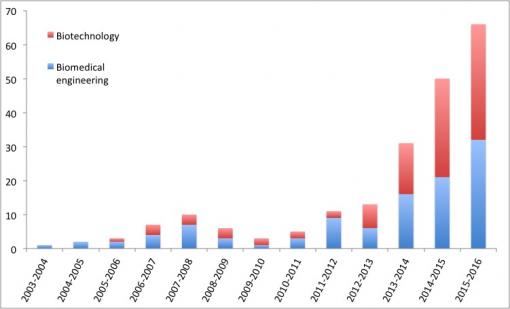

The trail Wojciechowicz followed to a master's in biotechnology had barely been blazed when she enrolled, but along with biomedical engineering, the program is rapidly becoming one of Brown's best beaten paths. In 2012, the two programs enrolled only a dozen students combined; this year they boast 65. In 2012, students from the programs earned 1.7 percent of Brown's master's degrees, but that jumped to 4.6 percent last year. That's a growing share of a growing pie, given that master's degrees increased from 479 to 520 over the same period university-wide.

Great Growth: Especially since the 2011-2012 academic year, enrollment in biotechnology and biomedical engineering programs has surged.

Brown's biomedical engineering and biotech boom is a product of the University investing in programs that have significant pent-up demand from students and employers alike, said program director Jacquelyn Schell, research assistant professor of molecular pharmacology, physiology and biotechnology.

"We realized there was a market for these degrees," Schell said. "Not only are students from all sorts of science backgrounds interested in these fields, but also the skills they learn from these two degrees are transferable once they join the workforce."

In 2013, CNN Money declared biomedical engineer the best job in the country. The industry is volatile, especially in the stock market, but even amid those fluctuations, New England's biotech employers were rapidly increasing wages in 2016 to compete for workers.

Realizing these trends were afoot, Brown hired Schell, an alumna, in 2012 to lead a rebirth in the programs. For years, it had been possible to get a Brown master's in these fields, but few students did. Schell has greatly increased the programs' visibility, but Brown's investment has gone well beyond getting the word out. In the last few years, Beth Zielinski, who directs industry outreach, helped to launch six-month paid co-op internships at 11 companies, and Schell and other faculty members have developed many new courses for the programs. They also launched a part-time degree for working students. The next development will debut in the fall: a track in biotechnology management for business-minded students.

Wojciechowicz applied for one of the new co-ops, which is how she got her start at Bard Davol. She earned a salary and course credit by participating in corporate research and new product development. When the co-op was over, the company hired her in December 2015 as an research and development project consultant.

Many paths to master

But Wojciechowicz's path is hardly the only one. While she earned her master's in a fifth year at Brown, two-thirds of the biotech and biomedical engineering master's students arrive from elsewhere. And while many pursue industry careers, more than half continue in academia after earning degrees.

There is, for example, a courses-only master of arts track in biotechnology favored by some pre-med students, but most of those who enroll are attracted to the programs' strong research focus, which prepares them for either doctoral programs or industry, Schell said. Of the eight required credits, students can fulfill three by writing a thesis based on working in a faculty member's lab. On average, students from the two programs have co-authored one peer-reviewed publication each.

"These students become an integral part of the research here at Brown," Schell said. "They put so much work into these research projects and they accomplish a lot. They are building the research enterprise here."

Kali Manning, who came to Brown after studying biomedical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, is a great example. Looking to gain a greater credential as an independent researcher, she considered a number of programs in New England but found Brown's especially appealing.

"The department seemed very welcoming, and at its core it was a community," she said. "Everybody is supportive. At a lot of research institutions, I've heard, it can be very, very cut-throat."

For her research, Manning joined the lab of Professor Jeffrey Morgan, who develops technologies for tissue engineering, a topic she studied at WPI. In 2014 she co-authored a paper on a prototype device for making large three-dimensional tissues. When Manning completed her master's in 2015, she continued in the lab as a doctoral student. Now she's working to figure out how to grow capillaries within engineered tissues. As the tissues become larger, eventually on the scale of whole artificial organs, engineers will need to grow vasculature within them to keep the cells within alive.

"I love the project," Manning said. "It's what I want to be working on."

Harry Cramer, now in his second semester of the biomedical engineering master's program, has similarly enjoyed his research and hopes to continue to a Ph.D. As an undergraduate bioengineering major at the University of California at Merced, he completed a capstone project working with a company on a method to turn agricultural waste into activated carbon for water filtration. In graduate school, he wanted to focus on medical applications. As a Connecticut native, he was happy to return to New England.

Now, as Cramer takes classes in advanced scientific imaging, he's also working in the lab of Christian Franck, an assistant professor of engineering whose studies include the effects of traumatic brain injury at the cellular level. Cramer's experiments are focused on developing a model of brain tissue mechanics. Neurons are embedded in a very uniform, collagen-infused hydrogel. Success will expand and improve the lab's testbeds for observing the effects of injurious forces on the cells.

It may not be fun for the cells, but Cramer said the work has been for him.

"I love the lab, the research, and the people in the lab are great," he said.

Whether viewed through the lens of individual stories or exploding enrollment, it's clear that these two programs are quickly proving to be in-demand options among the array of options for graduate study at Brown.

by David Orenstein