The technique is described in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The traditional method for studying cell movement is called traction force microscopy (TFM). Scientists take images of cells as they move along 2-D surfaces or through 3-D gels that are designed as stand-ins for actual body tissue. By measuring the extent to which cells displace the 2-D surface or the 3-D gel as they move, researchers can calculate the forces generated by the cell. The problem is that in order to do the calculations, the stiffness and other mechanical properties of artificial tissue environment must be known.

"Nowadays in tissue engineering, we can make really complicated structures that are much more like real tissues in the body, but because they're so complex we can't know all the mechanical properties," said Christian Franck, an assistant professor of engineering at Brown. "So we have these great tissue environments, but we can't use them to do our TFM calculations."

To come up with a new method, Franck worked with his students and Haneesh Kesari, a colleague in Brown's School of Engineering who specializes in solid mechanics.

"It was Haneesh who found this theory of what's called mean deformation," Franck said. "What that theory allowed us to do is build a framework similar to that of traction force microscopy, but without needing to know the mechanical properties. We can make calculations just by analyzing the images and seeing how the cell deforms as it interacts with its environment."

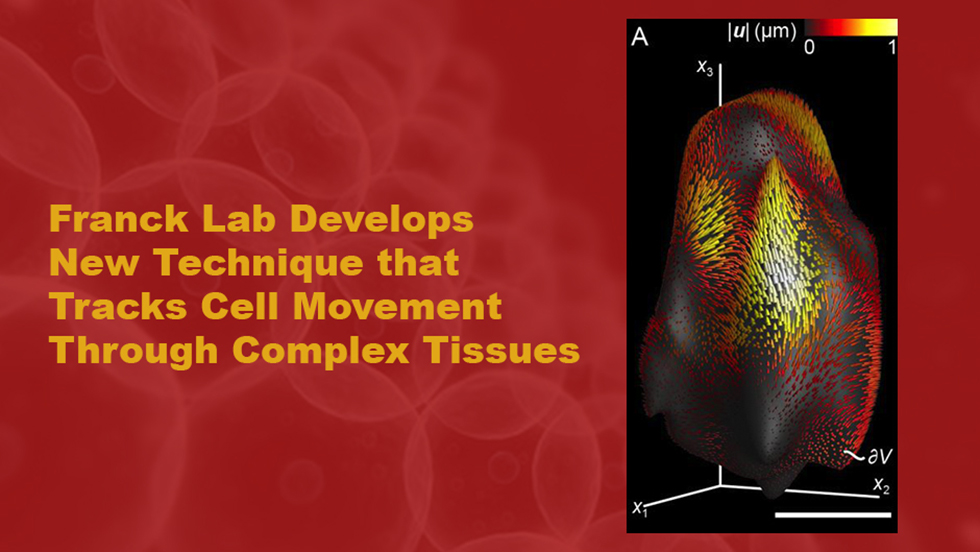

Imagine squeezing a rubber ball with your fingers. In each spot where a finger pushes on the ball, there's a depression. Mean deformation theory essentially adds up all those depressions and returns one quantity representing net change in shape across the entire ball. In cells, the theory derives a quantity by adding up all the places the cell deforms as it interacts with the tissue through which it moves.

"What's great is we get one simple quantity that's similar to the force quantity we get from TFM and we can derive lots of other quantities from it," Franck said. "We can do the same types of statistical analysis we do with quantities derived from TFM."

To see what the technique might be capable of, Franck worked with Jonathan Reichner, professor of surgery (research) in Brown's Warren Alpert Medical School. They imaged human neutrophils — white blood cells that play a key role in fighting infections — as they moved through a complex collagen matrix. Imaging was done on both healthy neutrophils as well as cells altered to mimic cells involved in septic shock — a potentially deadly dysfunction of white blood cells.

The work showed some intriguing differences between healthy cells and the sepsis model that had not been seen previously. For example, the algorithm suggested that cells in the disease state tend to be more contractile than healthy cells. They also tend to rotate as they move, whereas healthy cells do not.

"We were able to show significant differences between the healthy cells and the disease state," Franck said. "How those differences relate to the disease, we don't know yet, but we now have the ability to see these differences and to try to understand what they mean."

Franck and his colleagues plan to make the software that powers the technique freely available online for other researchers to use.

"All they need to use this are 3-D images," Franck said. "Once they have the images the software will analyze them."

In addition to Franck, Kesari, and Reichner, other authors on the paper were David A. Stout, Eyal Bar-Kochba, Jonathan B. Estrada, and Jennet Toyjanova. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM066194 and AI101469) and by a Brown University seed grant.

By Kevin Stacey

Knowing how cells move through different tissues in the body could be useful in treating conditions from cancer to autoimmune disorders. A new technique developed by Brown researchers can track cell movement in complex environments that mimic actual body tissues.

Knowing how cells move through different tissues in the body could be useful in treating conditions from cancer to autoimmune disorders. A new technique developed by Brown researchers can track cell movement in complex environments that mimic actual body tissues.