Perovskite solar cells are cheaper to make than traditional silicon cells and their electricity conversion efficiency is improving rapidly. To be commercially viable, perovskite cells need to scale up from lab size. Researchers from Brown and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory report a method for making perovskite cells larger while maintaining efficiency.

Perovskite solar cells are cheaper to make than traditional silicon cells and their electricity conversion efficiency is improving rapidly. To be commercially viable, perovskite cells need to scale up from lab size. Researchers from Brown and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory report a method for making perovskite cells larger while maintaining efficiency.

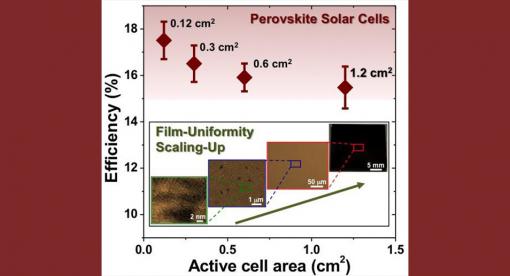

Using a newly developed fabrication method, a research team has attained better than a 15-percent energy conversion efficiency from perovskite solar cells larger than one square centimeter area. The researchers, from Brown University and the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL), have reported their findings in the journal Advanced Materials.

Perovskites, materials with a particular crystalline structure, have caused quite a buzz in the solar energy world. Perovskite solar cells are relatively cheap to make, and the efficiency with which they can convert sunlight into electricity has been increasing rapidly in recent years. Researchers have reported efficiency in perovskite cells of higher than 20 percent, which rivals traditional silicon cells. Those high efficiency ratings, however, have been achieved using cells only a tenth of a square centimeter — fine for lab testing, but too small to be used in a solar panel.

"The use of tiny cells for efficiency testing has prompted some to question comparison of perovskite solar cells with other established photovoltaic technologies," said Nitin Padture, professor of engineering at Brown, director of Brown's Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation, and one of the senior authors of the new research. "But here we have shown that it is feasible to obtain 15-percent efficiency on cells larger than a square centimeter through improved processing. This is real progress."

Maintaining high efficiency on larger perovskite cells has proved a challenge, Padture says. "The problem with perovskite has been that when you try to make larger films using traditional methods, you get defects in the film that decrease efficiency."

The fabrication process that the Brown and NREL researchers reported in this latest paper builds on a previously reported method developed by Yuanyuan Zhou, a graduate student in Padture's lab. Perovskite precursors are dissolved in a solvent and coated onto a substrate. Then the substrate is bathed in a second solvent (called anti-solvent) that selectively grabs the precursor-solvent and whisks it away. What's left is an ultra-smooth film of perovskite crystals.

In this new study Zhou and Mengjin Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at NREL, developed a trick to grow the perovskite crystals to a larger size. The trick is to add excess organic precursor that initially "glues" the small perovskite crystals and helps them merge into larger ones during a heat-treatment, which then bakes away the excess precursor.

"The full coverage and uniformity over a large area come from the solvent method," Padture said. "Once we have that coverage, then we increase the size of the crystals. That gives us a film with fewer defects and higher efficiency." The 15-percent efficiency reached in this latest work is a good start, Padture said, but there's still room to improve. Ultimately, he would like to reach 20 to 25 percent in large-area cells, and he thinks that mark could be within reach using this method or a similar one.

Padture and colleagues at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln were recently awarded a $4-million grant by the National Science Foundation to expand their perovskite research.

Other authors on the paper were Yining Zeng, Chun-Sheng Jiang, and Kai Zhu of NREL. The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AC36-08-GO28308 and DE-FOA-0000990) and the National Science Foundation (DMR-1305913).

- by Kevin Stacey